Abstract

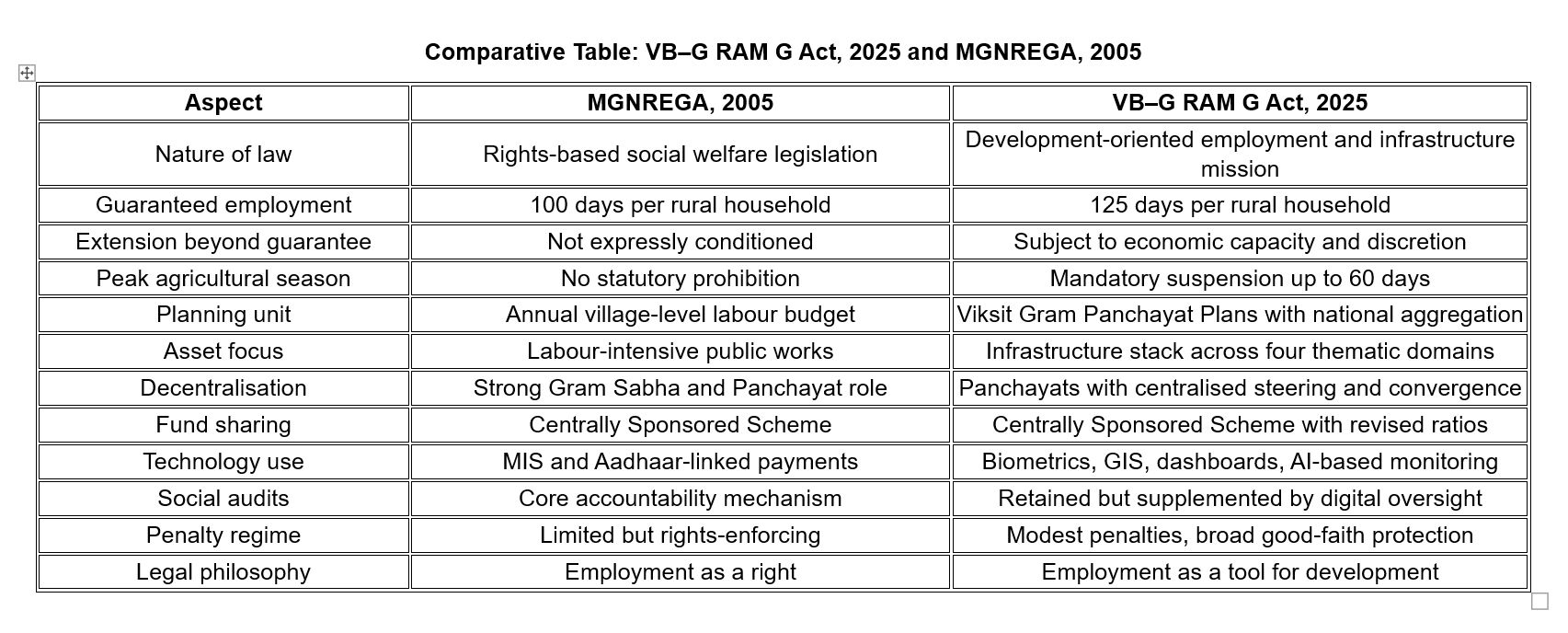

The Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025 represents a decisive shift in India’s rural employment jurisprudence. Repealing the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, the new enactment expands the statutory employment guarantee to one hundred and twenty-five days while embedding rural wage employment within a national infrastructure, convergence, and saturation-driven planning framework aligned with the vision of Viksit Bharat @2047. This article critically examines the Act’s legislative design, constitutional positioning, decentralisation framework, fiscal federalism implications, and technology-centric accountability architecture. It argues that the Act marks a transition from a rights-based social welfare statute to a development-oriented rural infrastructure mission, raising important concerns regarding conditionality of entitlements, centralisation of planning, digital exclusion, and dilution of grassroots accountability mechanisms.

Keywords: Rural employment guarantee; VB–G RAM G Act, 2025; MGNREGA; decentralisation; fiscal federalism; digital governance; Viksit Bharat.

I. Introduction

Since its enactment in 2005, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) stood as a rare example of a justiciable socio-economic right in Indian statutory law. The enactment of the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025 (VB–G RAM G Act) repeals this framework and replaces it with a more expansive yet structurally different rural employment regime. While the new Act enhances the guaranteed days of employment and integrates climate resilience and infrastructure creation, it also reorients rural employment away from a purely rights-based paradigm toward a mission-mode developmental architecture.

This paper undertakes a doctrinal and structural analysis of the VB–G RAM G Act, situating it within constitutional principles of social justice, decentralisation, and federalism, and critically comparing it with the repealed MGNREGA framework.

II. Legislative Objectives and Policy Orientation

The VB–G RAM G Act expressly aligns rural employment with the national vision of Viksit Bharat @2047. Unlike MGNREGA, which was primarily conceived as a livelihood security measure, the new Act articulates multiple policy objectives: enhanced wage employment, aggregation of public works into a National Rural Infrastructure Stack, convergence with other development schemes, and climate adaptation through infrastructure creation.

This explicit developmental orientation reflects a shift in legislative philosophy—from employment as an end in itself to employment as a means for long-term asset creation and rural transformation.

III. Employment Guarantee and Conditionality

Section 5 of the VB–G RAM G Act increases the statutory guarantee to one hundred and twenty-five days per rural household per financial year. However, the Act introduces explicit conditionality by permitting extension beyond the guaranteed period only within the limits of economic capacity and development. Further, Section 6 statutorily prohibits execution of works during notified peak agricultural seasons, effectively suspending the employment guarantee for up to sixty days annually.

This represents a departure from the on-demand character of MGNREGA and signals a recalibration of the balance between labour welfare and agricultural productivity.

IV. Planning Architecture and Decentralisation

While Panchayats continue to be designated as principal authorities for planning and implementation, the VB–G RAM G Act introduces a multi-layered planning architecture anchored in Viksit Gram Panchayat Plans and aggregated upward into State and National infrastructure stacks. Mandatory integration with PM Gati Shakti and geospatial platforms significantly constrains local discretion.

Although participatory planning is formally retained, substantive decentralisation is diluted by strong central steering committees, normative allocations, and binding national priorities, raising concerns under Part IX of the Constitution.

V. Fiscal Federalism and Fund Sharing

The Act retains the Centrally Sponsored Scheme model with revised fund-sharing ratios. Normative allocation powers are vested in the Central Government, and States bear liability for unemployment allowance and excess expenditure. This fiscal design strengthens vertical control of the Union and may disproportionately burden fiscally weaker States, thereby affecting uniform realisation of employment guarantees.

VI. Technology, Transparency, and Rights Implications

The Act mandates biometric authentication, geo-tagging, real-time dashboards, and artificial intelligence-enabled monitoring. While these mechanisms enhance transparency and efficiency, the absence of statutory safeguards against technology-induced exclusion is a critical omission. Authentication failures, connectivity gaps, and data governance concerns pose risks to vulnerable rural workers, particularly women, elderly persons, and migrant households.

VII. Accountability Framework

Accountability under the VB–G RAM G Act relies heavily on technocratic oversight and digital audits, supplemented by social audits conducted by Gram Sabhas. The penalty regime is modest, and broad protection for actions taken in good faith may weaken deterrence against administrative lapses. Compared to MGNREGA’s emphasis on community vigilance, the new framework privileges managerial compliance.

VIII. Repeal of MGNREGA: Continuity and Departure

Section 37 repeals MGNREGA while providing transitional continuity. Substantively, however, the repeal marks a normative shift away from employment as a justiciable right toward employment as a component of national development strategy. The transformation reflects evolving state priorities but risks undermining the rights-based legacy of rural employment law in India.

IX. Conclusion

The VB–G RAM G Act, 2025 is an ambitious and forward-looking statute that integrates rural employment with infrastructure creation, climate resilience, and digital governance. However, its centralised planning architecture, conditional employment guarantees, and technology-heavy compliance mechanisms raise significant constitutional and socio-legal concerns. The long-term legitimacy of the Act will depend on whether it can balance efficiency with equity and preserve the substantive right to work for India’s rural poor.

Leave a Reply