The Second National Judicial Pay Commission (SNJPC) was established in 2017 by the Supreme Court of India to assess and recommend changes to the pay scale and service conditions of district judiciary officers across the nation. Headed by former Supreme Court Judge Justice P.V. Reddy, with former Kerala High Court Judge R. Basant as a member, the commission aimed to ensure a fair and equitable remuneration structure for judicial officers. The primary goal was to rectify long-standing disparities in their compensation and improve the financial welfare of the judiciary at the district level, recognizing the pivotal role these officers play in ensuring justice is administered at the grassroots level.

In June 2022, the Supreme Court ordered the implementation of the revised pay scale proposed by the SNJPC, effective from January 1, 2016. A bench consisting of Chief Justice N.V. Ramana, Justices Krishna Murari, and Hima Kohli also directed that the arrears owed to judicial officers be paid in three installments: 25% within three months, another 25% in the following three months, and the remaining balance by June 30, 2023. In response to concerns regarding compliance, revised directions were issued in May 2023 to ensure that the Court’s mandate was fulfilled, further emphasizing the commitment to improving the conditions of judicial officers.

Currently, a key issue under deliberation before the Supreme Court is the applicability of Tax Deduction at Source (TDS) on the allowances provided to judicial officers under the SNJPC recommendations. This issue, which is sub judice, forms part of the ongoing proceedings in the All India Judges Association case. The case seeks to clarify whether the allowances granted to judicial officers, intended to enhance their financial and professional conditions, should be subject to TDS as per the provisions outlined in the Income-tax Act, 1961.

On July 15, 2024, during a hearing on the matter, the Court underscored the importance of resolving this question of taxability. Mr. N. Venkataraman, the Additional Solicitor General, informed the bench that the issue would be reviewed by the Revenue Department of the Ministry of Finance. The Court subsequently adjourned further deliberations to August 5, 2024, to allow the Ministry time to provide its findings. Given the sub judice status of the matter, its resolution is expected to have significant ramifications not only for the financial obligations of judicial officers but also for the broader administrative processes involving the judiciary and government.

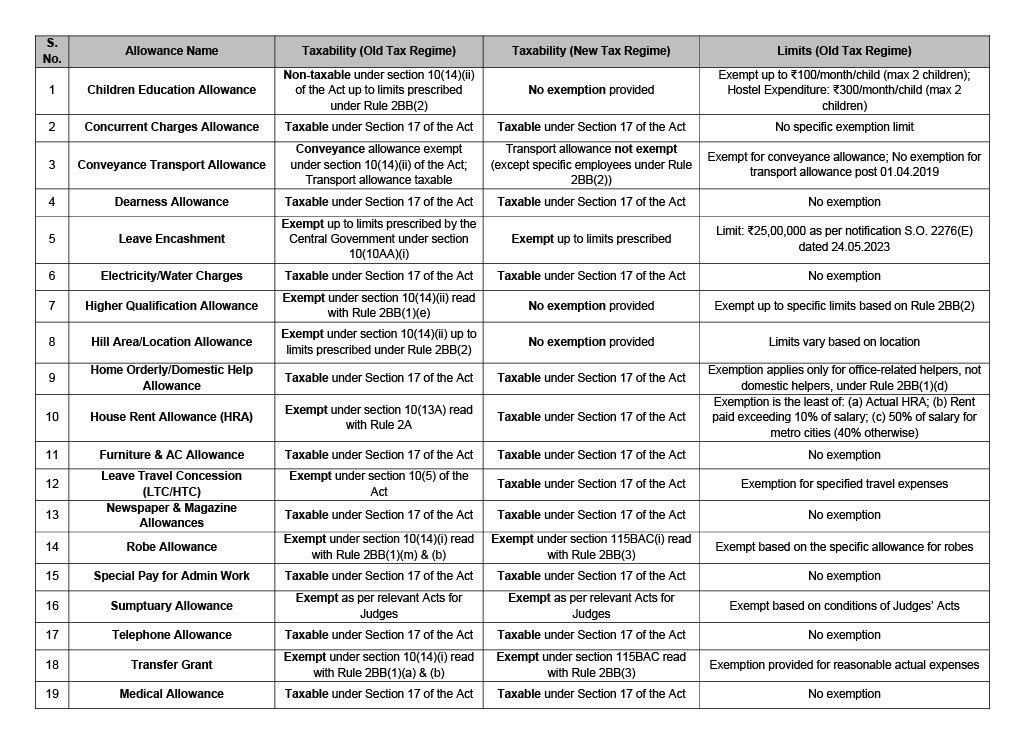

In the meantime, the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) under the Ministry of Finance issued revised comments regarding the exemptions from TDS for allowances paid to judicial officers under the SNJPC recommendations. This was formalized through an Office Memorandum (F. No. 275/67/2024-IT(B)), dated August 6, 2024. The memorandum provides insights into the taxability of various allowances granted to judicial officers under both the Old and New Tax Regimes, as governed by the provisions of the Income-tax Act, 1961 and the Income-tax Rules, 1962.

The memorandum is a vital resource for understanding which allowances are exempt from taxation and which may be subject to TDS. For clarity, the CBDT issued a comprehensive table outlining the taxability of allowances under both tax regimes. However, since the matter remains sub judice before the Hon’ble Supreme Court, the final determination regarding the exemptions from TDS on allowances paid to judicial officers will only be settled upon an authoritative ruling by the Court.

The ongoing deliberations reflect the government’s commitment to addressing the concerns of judicial officers and ensuring that their financial and professional needs are met in a fair and just manner. The resolution of the TDS applicability issue will undoubtedly have a lasting impact on the financial and administrative landscape of the judiciary in India.

![[Opinion] Justice or a Cruel Joke?](https://legisorbis.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/419c06d9-4d7b-4439-a888-9f152f974f1f.webp)

![[Judgment Analysis] Legitimate Dissent Must Not Be Confused with Sedition](https://legisorbis.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/788163bb-dcc0-4292-b7c2-1a8a23695a5b.webp)

![[Judgment Analysis] High Courts Can Quash Criminal Proceedings Invoking Article 226 Jurisdiction: Supreme Court](https://legisorbis.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/a2a61b70-7d5c-4ce0-a86f-c527c7f08a48.webp)

![[Opinion] Why Justice Nagarathna’s Call for Judges to Refrain from Social Media Is a Step Toward Upholding Judicial Integrity](https://legisorbis.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/1734021730714.png)